Looking Back and Smiling

Some Experiences in History Teaching

c1973 to c2013

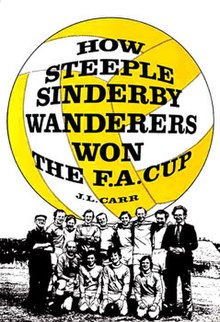

‘This isn’t the Official History. It is only a rough sketch for it. The Official History will be much longer, every detail will be double-checked to make sure it is the unvarnished truth …

It will also cost more.’

J L Carr, How Steeple Sinderby Wanderers Won the FA Cup, 1975.

In recent years I’ve been interviewed several times by researchers exploring the development of history teaching over the last fifty years. This has been a really strange experience. Even as I’ve been talking I’ve heard a voice in my head asking ‘Are you sure it was really like that? Are you just repeating what you remember telling the last interviewer? What have you forgotten?’ Being a primary source is a much greater responsibility than I’d ever imagined.

Then, when I’ve read the resulting history or thesis, I’ve felt that it’s all come out too neatly, in too ordered a way. Life, including history teaching, feels to have been much messier, more confused, more kaleidoscopic than a historian can possibly describe. Another deeply alarming thought!

Despite all that, this section of Thinking History contains a series of essays about history teaching for no better reason than I fancied writing them. In tune with J L Carr, I’m not trying to write an Official History, a Complete History of History Teaching since 1973. And there’s a few other things I’m not trying to do. I’m not trying to be up to date as I’ve been distant from history teachers’ debates over the last several years. I’m not trying to be scholarly and I’m not trying to be encyclopaedic. I’m not trying to draw up a table of successes. Instead I’ve chosen a handful of issues that matter to me, in which you’ll encounter a wide range of unintended consequences, a few happy accidents, a lot of enjoyable moments and sadly some unfulfilled aims.

I have tried to be honest but I can’t reflect all viewpoints, only my own. One thing I am aware of is that we are all good at identifying the nuances and qualities of our own teaching while caricaturing the work of those we don’t agree with. I have tried to avoid that trap, if only by not referring to other people’s work and views.

Finally – the community of history teachers has been as good and inspirational a bunch of people to spend my working life with as I could possibly have wished for. A late bonus has been getting to know so many younger teachers (though some may no longer think of themselves as young!) who have been more than generous in welcoming me to listen into and even contribute to their discussions.

For Angela, Ann, Chris, Jane and Kate and in memory of Ian – inspiring examples all.

Download the Essays

1. A Happy Choice: how history teaching grew on me and made me smile HERE …

2. Why I found SCHP so exciting in the 70s: did it achieve what I hoped for? HERE …

3. Abdelsebhor, Aswan and why I think it’s important to teach history HERE …

4. Disappointments and Frustrations – Things That Got Away From Me HERE …

5. Creativity in History Teaching HERE …

6. The Accumulated Happiness of a Teaching Lifetime HERE …

7. A Letter to My History Teacher HERE …

8. The Pleasures of Belonging to the History Teaching Community HERE …

Endpiece

I didn’t have a title for these essays when I began though I confess I was thinking more in terms of ‘Looking back and being Grumpy’ than ‘Looking back and Smiling’. I was worried about making too many generalisations, that perennial bug-bear of historians, but my first ideas looking back at my involvement in teaching made me feel like an unsuccessful juggler. I’d kept a couple of balls in the air but had a large pile round my feet where I’d dropped them. Happily, both the thinking and the enjoyment of writing have helped me feel very different – I feel recharged, by the happy memories but also by the process of getting so much out of my head onto paper and the website.

Aside from the therapeutic value of writing, one thing that now stands out has been the continuing presence of two ‘conflicts’. The first has been my desire to focus on the human element, individual lives and experiences, which has been a struggle at all levels because of the unrelenting quantity of content to cover. The second conflict has been between immediate demands created by curriculum and assessment revisions and, on the other hand, the achievement of bigger aims and ideals which are not assessable and therefore too often fell by the wayside.

My other and final very personal conclusion is that I was surprised to discover how idealistic I still feel. Not long ago I came across this quotation from the writings, in the 1930s, of Eileen Power, one of the great medievalists of the 20th century:

‘History is one of the most powerful cements known in welding the solidarity of any social group …If we can enlarge the sense of group solidarity and use history to show the child that humanity in general has a common story, and that everyone is a member of two countries, his own and the world, we shall be educating him for world citizenship.’

That’s obviously an aim of its time but the idea that history teaching can do good was still around in the 1970s. In many ways history teaching has changed for the better over fifty years – teachers use a much wider range of resources and techniques, they think hard about how to help students learn and take responsibility for that learning, they are far better at helping students do well in assessment and themselves have more sophisticated knowledge of how to help students understand the discipline of history. They can draw upon a wide range of discussions about history teaching which (thankfully!) was much, much slimmer fifty years ago. There is so much brilliant CPD on offer. As a result of all this, many students enjoy studying history because of the way they’re taught, not despite the way they were taught which was so common when I was at school in the 60s.

But … how much has really changed? Does Anglocentric history still dominate KS3 to an extent that is inappropriate in a world where people are hugely more mobile and linked to other cultures? Do the same ‘big topics’ dominate KS3 without sufficient use of outline enquiries to help students develop understanding of chronology and themes across time? Has external assessment at 16 become much more restrictive –in the 70s when we had coursework, mode 2 and 3 CSEs and there was even a brief golden age when examiners experimented with questions without stirring howls of protest? Have publishers moved on from filling their books with quickly out of date guidance on how to do well in exams? Do exam specifications reflect the latest approaches in historical research? Do GCSE students know why some of their courses are studies in depth and another is a thematic unit and there’s also something on the historic environment tucked in there – do they understand and can they explain the reasons for this variety of approach? And finally, the biggest question of all for me - Do students of all ages still struggle to understand why history can help them understand their world?

Maybe that list of questions explains why I felt grumpy when I started – before I wrote these essays – but I’m not grumpy any more. I feel recharged by looking back over the trajectory of the last fifty years and seeing the positive elements, not just the difficulties. The writing itself has released energy and excitement, as it always does when I’m writing in my way. I don’t feel weighed down by the implications of age, unable to write any more resources because I’m too old. I do want to pick up some of those ‘disappointments’ and get stuck into turning them round, for my own satisfaction if no-one else’s. And I need to get back to the 15th century to revisit the Pastons and the Redmayns.

I can recommend looking back and writing about the past,

therapeutic history it must be called.