Bob Unwin – An Appreciation

Such a warm, phenomenally energetic and encouraging man.

Legions of history teachers were inspired to share the history around them.

I feel genuinely privileged to be one of them. (Judith Kidd)

I am grateful to Bob’s son, Dr Pat Unwin, for providing the biographical passages (in italics) and to the teachers who have contributed their memories of Bob. I hope all these elements combine to create a worthy appreciation of a man who inspired so many of us through his example, support and kindness.

Ian Dawson, February 2021

You can download a PDF of this tribute HERE …

Bob Unwin

History was struggling in many schools in the early 1970s. ‘History in Danger’ became something of a cliché but at the time the danger was all too tangible for many of us starting out in teaching. These were the ROSLA years – when the Raising of the School Leaving Age to 16 meant that for several years there were many teenagers who felt ‘stuck’ in school, for whom History (what’s the past got to do with us, sir?’) was an obvious target for derision and hostility. Worse, because it felt a long-term shift, History at KS3 was being bludgeoned into invisibility in schools such as the one where I taught, by concoctions of Integrated Studies (though integrated was one thing they were not). Teachers’ morale fell because we weren’t teaching the subjects we loved and because of the consequent fall in the numbers of exam candidates. This context may seem an odd way to begin an appreciation of Bob’s contribution to history teaching but we can’t understand the role he played without awareness of the atmosphere enveloping history teaching at that time.

Credit for the turnround in History’s fortunes is often given chiefly to the Schools Council History Project, founded in 1972, but in the 70s SCHP had more critics than supporters. Instead, on a region by region, local authority by local authority, school by school level much of the revitalisation of History was the result of the inspiration provided by individuals such as Bob Unwin, PGCE tutor, author, conference and workshop leader, historian, innovator and enthusiast par excellence.

In fact, there was no-one quite like Bob.

Looking back from my vantage point, having been involved in history teaching since 1973, I have no hesitation in saying that Bob was one of the most significant contributors to history education during the last fifty years. Bob’s death in January 2021 has saddened all those who knew him and were trained by him and who, looking back, appreciate just how much he contributed to our teaching careers and personal satisfaction.

Bob was born in 1938 in Hillingdon and graduated in 1961 with a BA in History from the University of Hull. He spent his early career as a teacher and head of history in several schools in Yorkshire. During this time, he completed his first PhD thesis (Hull, 1971) on ‘Trade and Transport in the Humber, Ouse and Trent Basins from 1660-1770’. Bob was appointed as lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Leeds, in 1972, where he remained until his retirement in 2002. During his early time in Leeds, he embarked on a second PhD on ‘Education and society in Wetherby and its environs, 1660-1902’ (1979). Henceforth, he also became known as “Dr Dr Unwin” to his PGCE students, although always liked to be known as “Bob”.

Meeting Bob as a trainee in 1973 was revelatory. Until then, my experience of teaching was based on how I’d been taught – five years of dictated notes at grammar school, followed by two years of taking more relaxed notes at A level. Imagine then sitting in a lecture theatre, expecting to take notes yet again, when into the room surges Bob brandishing a chunk of raw wool. How, he wanted to know, would we use this wool to start a lesson on the Industrial Revolution? Until then, my classroom experiences had been the equivalent of village cricket – the pace at which Bob talked and thought propelled me into the middle of a test match. No more mental jogging. I had to start sprinting.

By the end of that session we had no doubt – Bob was a firecracker, the epitome of human energy. His conversation raced along, seeking out the next idea or discovery, always accompanied by what I can only describe as a continuing conversational chuckle. He was a constant innovator, passionate about developing teaching methods that would challenge and enthuse pupils, an expert at developing novel approaches to resources and textbooks, a champion of fieldwork, local history and the use of sources, especially visual sources, and he espoused computers at an early stage. But there was nothing shallow about Bob’s innovations, as befitted a man with two doctorates acquired amidst his work as schoolteacher and PGCE tutor. As trainees we were in awe. How could anyone be so energetic? How could he create so many resources? Did he ever sleep?

Bob established a reputation as an inspirational tutor, teacher and communicator, enthusing thousands of PGCE students, who flocked to Leeds University to study with him. As Professor David Hicks (Virginia Tech University), and one of his PGCE students (1988-89) observed in his PhD thesis (VTU, 1999): Bob was a ‘quick-witted whirlwind of activity and ideas who stressed the importance of guiding and involving students’ in the classroom and whose ‘methods course at Leeds had a major Influence on developing practical ideas and goals for teaching’. From the 1960s onwards, Bob was a pioneer who believed passionately that school students should have access to, and analyse, primary historical sources themselves and become empathetic. The teacher was the guide, who should respect the learner and their ability. These were revolutionary ideas at the time.

In the words of some of his trainees:

I absolutely loved Bob at Leeds University. He observed me teach a number of times and played a big part in my development. I loved his guided historical tour of Leeds. I’ve taken my family on it a number of times! (Tim McGrath)

He was an inspirational tutor who showed me, and thousands of other students, the way primary sources could be used to inspire pupils. An influence that lasted for the rest of my career. (John Lawson)

Such an inspiring, enthusiastic & passionate man. I think of him often and the impact he has on my teaching. I was awarded the June Wenban award for teaching when training with Bob, was due to him. (Luke Zwalf)

Part of Bob’s significant impact stemmed from his exuberant and infectious enthusiasm, History teaching was (is!) absolutely joyous. His mentoring was positive, encouraging and also very practical. He metaphorically and literally rolled his sleeves up, giving his trainees confidence and offering incisive adaptation to transform our very first lessons: sharpening a question, ways to build a relationship with a challenging student or thinking more about the knowledge required to appreciate the nuance of a historical source. Many of us trainees had to make an accelerated transition from naïve recent graduate to credible professional in such a short space of time but we quickly gained self-belief and had rigorous professional thinking modelled for us (at pace!) by Bob. His practical support always had absolute academic purpose and was rooted in knowledge without compromise. Knowledge, disciplinary thinking and the dynamic interaction between past and present that History brings – Bob taught us what could and should be an entitlement for all students. (Judith Kidd)

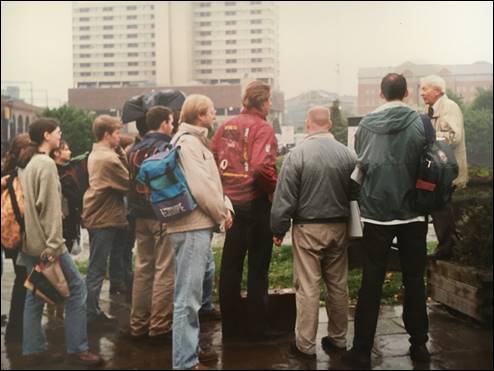

Bob’s walking tour of Leeds included learning about the horrors of the C19th courts, the majesty of Leeds Town Hall and the wonder of Temple Works. I think Bob used to walk/scurry far more quickly than people less than half his age were comfortable with. As a tutor he was always encouraging, perhaps giving more praise than really deserved. One thing that has particularly stuck with me, from what was probably my first formally observed lesson, was him pointing out that I hadn’t made eye contact with two quiet pupils at the back throughout the lesson. 28 years later I still think of the importance of eye contact in my own and others’ teaching, citing Bob when I give feedback to trainees. Reading that back, I see it’s very prosaic, but I’m sure there will at least hundreds of people teaching today who are conscious of, and perhaps pass on, their own little pearls of wisdom from Bob. (Henry Walton)

Bob took us on a guided tour of Leeds city centre at the start of our PGCE, and was accosted by a surly drunk on the steps of the town hall. Bob had charmed him utterly within 5 mins and they chatted happily like old pals until we moved on. LEGEND. (Sarah Faulkner)

The legendary walking tours of Leeds were an emblem and so representative of Bob’s animated, rich and interactive approach to communicating History. Thousands of History teachers will not be able to walk past the Adelphi pub or view the horizon of chimneys approaching Leeds on the train without thinking of them. Bob’s tours physically modelled how new teachers could literally open up their historical environment, on whatever scale, with humour, lively connections, big picture narrative, subtlety and, of course a rapid pace. They were not cosmetic hooks. And thousands of field visits, nationally, will have been so inspired (but poorly imitated!) (Judith Kidd)

Bob’s help didn’t end when we finished the course. When I returned from VSO in Aswan the following summer, jobs were scarce and the only one available was in a notoriously problematical school. I phoned Bob, more than half-hoping he’d advise me to wait for a better option. No chance! Bob’s advice was to take the tough school. I’d learn more there in a year than I would in several years in many other schools. He was right. I had a horrendous first year but five years later, when I did leave, I hated doing so and I’d learned more than I could have imagined.

Being an inspiration to 30 cohorts of trainees was however only part of Bob’s impact on history teaching. Through his books, resources and contributions to national conferences he also influenced teaching throughout the country. Bob was history consultant for the Yorkshire TV series How We Used to Live – a highlight in classrooms all over the country at a time when we had so few resources other than books and the teachers’ voice.

It was for his pioneering school texts and resources that Bob was best known. His ground-breaking Handling History kits (Hutchinson, 1975), on the Pre-Industrial and Industrial Ages, provided the classroom with an integrated resource in a box: a Teacher’s manual, 15 archive booklets (for collaborative work between 2 pupils) and workcards on 40 topics, all richly illustrated, and with thought-provoking questions to encourage the pupil-researcher. He was series editor and wrote two of the books for ‘Openings in History’ (Hutchinson, 1979), in which the opening to each topic is a pictorial or material object, an eye-witness account or a diagram, which pupils explore through structured questions and exercises…before reaching the narrative’, so as to reinforce the learning. These were followed by his two books titled Britain Since 1700 (‘History for You’ series, 1986) and Questions of Evidence (Stanley Thornes, 1988), which were very popular GCSE texts. Among his other publications was the Oxford Primary History series (Key Stage 2), which he devised and edited; with his wife, Patricia, he also wrote Tudors and Stuarts for the series (OUP, 1994).

Context again is important – when Bob began writing for publication and created resources for his own classrooms, there were no word processors, just typewriters. Even photocopiers were in their infancy (as trainees in 1973 we did not have access to photocopiers!). Writing books for publication was a drawn-out business. Successive drafts were typed and sent by post, proofs consisted of text cut out of galleys and pasted onto sheets of paper with glue. Picture research was laborious. I remember meeting Bob one day in the university library, leafing through a vast pile of copies of History Today to find images for a new textbook. No google searches back then.

In these circumstances it’s not surprising that Bob was an enthusiast for the possibilities of technology. Mike Maddison, history teacher and later a highly-regarded HMI recalls:

We had a first rate trainee from his course who was doing well on his school practice. Bob, though, wanted to ensure that this trainee was always scanning the classroom and not just focusing on those in front of him. So he arrived one day with an ear piece and a mic – the trainee had the ear piece hidden beneath long hair, Bob had the mic hidden under a scarf he wore even though it was a warm room! Throughout the lesson (which I also sat in on) Bob would whisper into his ear piece about pupils who were going off task and the trainee quickly challenged these pupils. Even though he had only been taking this class for a couple of weeks, the trainee managed to challenge one recalcitrant pupil by name even though he was writing on the board and had his back to the class. The pupils were amazed and never twigged what was going on. The lesson of course was to be aware of everyone in the room and to be constantly scanning for who was on or off task – a great learning point for the trainee and achieved with the use of new technology!

Mike also remembers another role Bob played – that of opportunity provider:

In 1988 I became an examiner at GCSE. The following year I became a senior moderator and the assistant principal examiner for the modern world course for NEAB (as it then was), and I remained in examining at GCSE and A level until 2002. After a couple of years I mentioned this to Bob and he immediately invited me in to talk to his trainees about GCSE history. I suppose this was my first public speaking engagement about history and I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was the start of an interesting aspect of my career and speaking to groups of teachers and trainees has always been one of a favourite and most rewarding parts of my life.

Other local heads of department were asked to contribute their expertise to PGCE classes in the 70s and 80s which not only gave the trainees the chance to hear other perspectives and ideas but was a great boost to the confidence of the teachers who received these invitations. Other teachers had their first chance to speak at CPD events such as the day conference Bob organised at the university for many years. I have particular reason to be grateful to him for he gave me my first chance to contribute to a CPD course and my first chance to write for publication. It was a great feeling, realising that Bob Unwin had confidence in me to do these things. And I was far from the only one as Judith Kidd explains:

Looking back on the influence of my own training year and the subsequent contact I had with the Leeds University PGCE course, it is clear that Bob’s legacy was also about promoting the dynamic and inclusive, professional culture of the History teaching community. Bob didn’t wear his research, publishing or speaking work as a badge. He loved sharing his explorations, we could do the same, however modest, and encourage our mentees and colleagues to do likewise.

And then there was Bob’s work for the HA, described by his son Dr Pat Unwin:

He organised conferences and workshops, gave many lectures at HA meetings and published a very well-used and innovative booklet on The Visual Dimension in the Study and Teaching of History in School (1981) that highlighted his long-held ideas about the importance of various types of illustrations for teaching. He also wrote Teaching the Victorians at Key Stage 2 as part of the ‘Bringing History to Life Series’ (HA, 1994). Away from schools Bob was the founding editor in 1983 of the HA’s magazine The Historian. From the outset, The Historian was to be ‘an up-to-date and forward-looking magazine, provided by and for all historians’. For the following 10 years, Bob provided thought-provoking editorials and leadership, his final issue being number 38, with an editorial on ‘Turning Wheels on History’s Journey’.

Bob’s books and academic articles showed diverse interests, but focused particularly on social history. He was a real stickler for detail and spent a lot of time poring over records. His book ‘Wetherby – The History of a Yorkshire Market Town’ (1992), is something of a model for the history of an English market town. He also wrote several articles on James Talbot, ecclesiastic, educationalist and musician. There was a super piece on "Charity Schools and the defence of Anglicanism: James Talbot, rector of Spofforth 1700-08" Borthwick Paper 65, University of York (1984). Talbot's manual "The Christian Schoolmaster", popular in the eighteenth century, was conceived and written in Spofforth, and the paper examines the extent to which the local parishes were receiving the benefits of schooling. Bob also wrote "Patronage and Preferment: A Study of James Talbot, Cambridge Fellow and Rector of Spofforth, 1664-1708" for Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, 1982, and "'An English Writer on Music': James Talbot 1664-1708", The Galpin Society Journal, 1987. This journal focuses on research into the history, construction and use of musical instruments. On a very different geographical scale, Bob was the UK’s historian for the Illustrated History of Europe (Weidenfeld Nicolson, 1992), a unique collaborative project by historians from each of the (then) twelve members states of the EU, which is still in print.

In his later “retirement” years, Bob developed a keen interest in the history of science, publishing academic articles with his children, Prof. Patrick Unwin and Dr. Tessa Mobbs. Bob's interest in the history of science developed through his work on local men of science and probably started with his study: "A Provincial Man of Science at Work: Martin Lister, FRS and his Illustrators 1670-1683", Notes Rec. R. Soc. London, 1995. When he retired, I suggested that he and I should do something together on the history of electrochemistry (I lead a group at Warwick focused on electrochemistry, and love the fact that it is one of the most important subjects for the 21st century – batteries, fuel cells, sensors, electrosynthesis, etc.) and has an incredibly rich history, going back several centuries. We decided to look at Humphry Davy, who has been written about extensively, but we found some interesting new things to say. Our paper, " 'A devotion to the experimental sciences and arts': the subscription to the great battery at the Royal Institution 1808-9", is classic Bob detective work. Without going into detail, Davy was arguably the most famous scientist at that time (certainly in England, and had made some spectacular discoveries. However, he desperately needed a new battery (not least because Napoleon had provided one from state sources for French rivals)! Despite Davy's great successes, the managers at the Royal Institution had to set up a public subscription. The raising of funds had been written and talked about as a great triumph, but through research in the RI archives, Bob was able to compare the subscription list with a list of those who had actually paid up (and the timescale), and it was not quite as had been assumed! I think it's a great piece for highlighting generally the issue of funding of 'big science', which echoes through history to the present time. Our piece, "Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution of Great Britain", Notes Tec. R. Soc., 2009, looks at the reforming aspirations of Davy with regard to the RI, which was relatively young at the time.

With my sister, Dr Tessa Mobbs (a mathematician, who now works in Administration at Leeds U), Bob wrote on Charles Babbage, Notes Rec. R. Soc. 2013 and, most significantly, "The Longitude Act of 1714 and the Last Parliament of Queen Anne", Parliamentary History, 2016, Vol. 35,. This challenges the popular history by Dava Sobell, which links the Act to a British naval disaster off the Scilly Isles in 1707, and puts forward a sophisticated multicausal argument for the Act (classic Bob!)

It’s felt important to include those details of Bob’s historical research and writing to build a better sense of the breath of his interests and his life and to show those of us who only knew him through teaching that his many educational contributions over-lapped with and were followed by many years of achievement and enjoyment in areas we knew nothing about. When I last met Bob eighteen months ago, by when he must have been eighty, I still found myself having to set my brain to ‘sprint’ to keep up with his conversation as he bubbled with enthusiasm about his research into the history of science in collaboration with his children. It was a wonderful reminder of the energy that had so impressed me over forty years earlier but with Bob his energy always had a purpose – improving historical education so that pupils could learn to love and be challenged by their study of History. Thirty cohorts of trainees, many more teachers throughout the country and many, many thousands of pupils have great reason to be grateful to Bob. Through them, new generations of teachers who never met Bob have been influenced by his work.

For all that, we can only say a very inadequate ‘Thank you, Bob.’