STAGE 1: When the work is set – establish clear success criteria

When planning new units (such as thematic units or depth studies at GCSE) it is essential to have a clear idea of the outcomes you want to achieve. Rather than starting from the textbook or your favourite activities, start with the desired pupil outcomes. Move from the outcomes you want to see, back to the learning intentions and success criteria, then to the activities and resources that are needed to meet the success criteria.

Further advice on planning thematic studies and depth studies is provided here:

Key Principles for Teaching Thematic Studies at GCSE HERE …

Planning Principles for Teaching Depth and Period Studies HERE …

A clear understanding of the success criteria is just as important for the pupil as it is for the teacher and it forms the crucial first step in our 6 stage feedback cycle. This stage is informed by three key principles:

1. Visible Learning: students need to ‘see’ what a good response to the task looks like

2. Co-construction: pupils should be actively involved in the construction of the success criteria

3. Transferability: pupils need to be able to transfer ‘generic’ criteria to new learning contexts

Visible learning

We should avoid a tokenistic approach to sharing success criteria. It is important not to rush this crucial stage of the feedback cycle. For students to make progress they need to be aware of the gap between where they are and where they need to be. A photocopied list of criteria, handed out with limited explanation or discussion can confuse pupils. Instead, we need to make sure that students are given time to think through what the criteria means in practice and to ‘see’ what the end result looks like.

It is therefore crucial to make sure that all students know what quality work looks like. Modelling the success criteria benefits lower-achieving students the most. Many higher-achieving students already have a clear idea of what successful work looks like but others do not. For improvement to occur the student must have a concept of quality roughly similar to that held by the teacher. This means that deconstructed, annotated examples of high quality responses should be on display, available in the classroom (perhaps laminated and in placed in pockets on the wall) and accessible from home via a learning platform. Models of excellence (especially those produced by a previous year group or another class) can create high expectations, inspire students and create the ‘can do’ mentality in the classroom.

Co-construction

As much as possible, students should be actively involved in devising the success criteria with the teacher and have the opportunity to apply the criteria to their own work. Our most common approach is to start with a good model (this could be from the work of a previous class, a model provided by the exam board or an exemplar produced by the teacher). Use this model to identify the key features of an effective piece of work. Key features identified by the students then form the basis of jointly constructed success criteria that the students feel a sense of ownership with. This type of approach means that students will be far more likely to apply the learning intentions and success criteria to their own work.

Generic versus task specific feedback

Detailed, task-specific success criteria can be counterproductive. If you specify in detail what students are to achieve you are in danger of providing a straight-jacket that restricts thinking, limits opportunities to learn from mistakes and reduces the chance of students constructing original lines of argument. We therefore need to think carefully about how we model success criteria and the amount of support we provide pupils when they work towards them.

Also, to be successful at GCSE and A level history, students need to be able to transfer their learning to a different context. During the learning it is therefore important to build in a degree of generality into the success criteria – so as to promote transfer across tasks. Enquiry is at the heart of Key Stage 3 History – it should be at the heart of the GCSE and A level courses too. Ian Luff argues that only if we assess through structured enquiry alone do we assess history holistically (See Teaching History Feedback and Assessment edition, 2016).

It therefore seems to make sense to build in generic, enquiry-focussed success criteria to each task. These could focus on the key steps in the enquiry process:

• Decoding questions: Has the student identified the conceptual focus of the question? Do they focus on the right chronological period? (click on the image alongside)

• Research and use of sources: Has the student used a range of sources? Do they consider the provenance of the sources? Have they selected appropriate information and deployed it effectively to support arguments?

• Construction of argument: Has the student considered a range of arguments? Are these evaluated in order to establish a clear line of argument?

• Organisation and communication of ideas: Has the student used paragraphs to organise their work effectively? Is the piece of writing coherent? Does it show a developed historical vocabulary?

History progression grids like the one below can help pupils get a better idea of what getting better at history looks like.

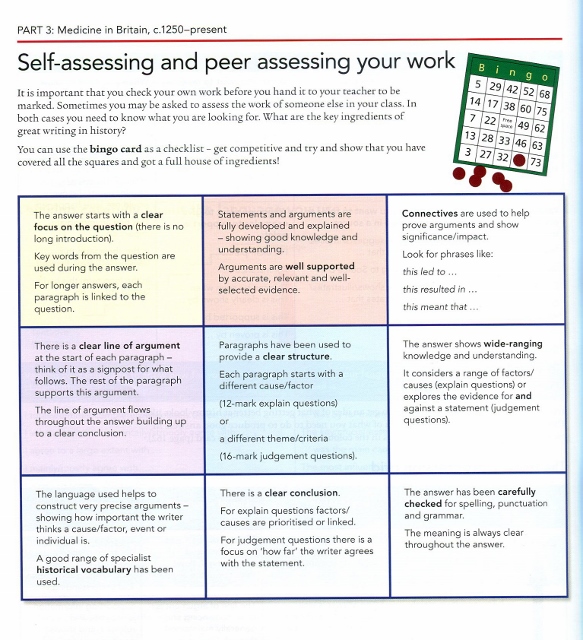

These can be developed into bingo cards that can be used to establish consistent, generic success criteria for most answers. An extra line can be added to provide task specific criteria when needed. These bingo cards can also help to focus self and peer assessment, as well as teacher feedback and target setting.

Additional strategies for developing pupils’ understanding of success criteria

• The teacher provides 5 samples of work from last year’s classes. Pupils work in groups to decide whether some are better than others and give reasons for their views. This feeds into the whole class construction of success criteria.

• Using work produced by previous classes (or models produced by the teacher) students work in pairs and then groups of 4 to spot errors and weaknesses in the responses. Pupils tend to be better at spotting errors and weaknesses in the work of others rather than their own! They use their findings to produce a ‘What Not to Write’ checklist which can used for self or peer assessment.

• Students complete a question or task for homework and hand it in to the teacher. In the next lesson they are then given 3 copies of successful essays. In small groups they discuss why they have been judged as high quality, thus identifying the key features of a successful answer. They are then invited to redraft their own piece of work before it is ‘marked’ by the teacher. This is useful because it provides a concrete example of excellent work and students can compare their own work with the samples provided before ‘closing the gap’ between their own work and the ‘models of excellence’.