Building A level students’ confidence and ability as learners:

Writing and Editing A Level books 1990-2015

Introduction

I was involved with three series of A level books as writer and editor – and 17 books in all. I don’t know if that sounds a lot of books, but it was certainly a lot of pages – most were big books. I began with writing The Tudor Century 1485-1603, a hefty 424 pages published in 1993. I then edited the nine books in the Core Text series for John Murray/Hodder between 1998 and 2006. They varied in length between 280 and 450 pages. Finally I was given gentler tasks. I wrote, as I’d long wanted to, The Wars of the Roses, again for Hodder in 2012 and edited six of the other books in that Enquiring History series, all of 144 pages. (The full list of titles in these series is at the end of this article)

None of these books were written for individual specifications nor contained assessment guidance.

The focus of this article is how we went about helping students to learn more effectively – the nature of the books was a product of focussing on learning as well as the history itself although, given that number of pages, they certainly contain a lot of history. My key idea was that I was creating what I call ‘stepping stone’ books so I’ll begin by explaining what I mean by that term.

Stepping Stone books: What was I aiming to achieve?

I never saw my books as being ‘the only book you’ll need’ for A level but as ‘stepping-stone’ books, the first stage in helping students towards a wider range of reading. I aimed to create books that immediately felt accessible to new A level students, especially less confident students for whom History was their second or third choice A level or whose GCSE results hadn’t lived up to hopes – the students who might fall by the wayside if their confidence dipped to critical levels early in their course.

As a young teacher in the 70s there were very few immediately accessible books for such students – mostly we made do with large tomes (such as the intimidatingly huge, black-backed Oxford Histories) which needed a lot of mediation to help students cope with them. It was obviously important for students to use demanding books but some never made the leap to being able to use them effectively – hence my wish to create stepping-stone books that encouraged students to believe that they could use more extensive, discursive texts, that they could cope, learn and thrive with the right support. One important criterion for success was, therefore, for these books to help students towards the books and articles that would enable them to reach higher standards than they’d expected and which they would go on to use at university.

Download this article in full

This webpage presents only the introduction and concluding reflections.

A PDF of the full discussion, covering the different series, can be downloaded HERE …

Do these A level books have a value as CPD for teachers?

Teaching A level students is deeply enjoyable and rewarding - and just as technically demanding as teaching younger students. It’s easy to think, when you start out teaching A level, that it’s chiefly about ‘delivering’ knowledge and exam technique to students. It’s certainly true that the depth of knowledge needed by teachers is intimidating, especially if it’s a new topic for you, but what makes A level teaching technically demanding and, as a result, deeply fulfilling is the need to focus on how to help students learn, both about the history and about how to study history.

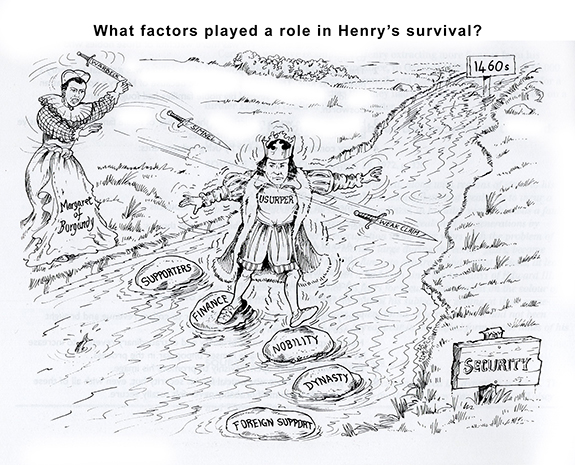

I’ve always liked this artwork created by the authors of The Early Tudors 1485-1558 and I’ve included it here because it links my concept of ‘stepping stone’ books to the value of these books as CPD for new teachers of A level. Imagine the figure of Henry VII in the centre is an A level student trying to progress across the A level river from the beginning of Y12 (when he or she is still very much a GCSE student) to success at the end of Y13. On the bank, instead of Margaret of Burgundy hurling knives, there’s a figure representing the voice in the student’s head, hurling knives saying ‘self-doubt’, ‘this is harder than I thought’ ‘you didn’t do well with that last essay’ and other confidence under-mining thoughts. What the student needs is help – those stepping stones put in place by the teacher to provide help, guidance and confidence. What would that help consist of?

My first stepping stone is obviously books that get students off to a confident start – that’s what this article has been about – and encourages them to believe that they can cope with the depth of knowledge and understanding that’s needed. Other obvious stepping stones are the teacher’s knowledge of the history and of how history is studied, their ability to narrate and explain clearly and to enthuse and create curiosity and their capacity to improve students’ ability to tackle exam questions and coursework. However, there’s other, maybe less obvious stepping stones too, ones that I tried to build into my A level books. Here are three of them, all very much about building students’ confidence as learners.

1. Developing independence as learners – one of the most stabilising stepping stones is helping students become confident independent learners. This requires students to understand and use the enquiry process of question, begin reading, hypothesise, read and research in more detail, revise hypothesis, decide how certain their answer is etc. If you can embed this in students’ practice it’s a huge help in crossing that river because it greatly reduces the chance of them developing that ‘I feel lost, I don’t know what to do next’ feeling that is so undermining - and independent learning will help them cross the tumbling torrent that is study at university too.

I’ve discussed this model in an article HERE … using the best example I built into my A level book on The Wars of the Roses – don’t be put off if you don’t know anything about the 15th century it’s the example of how we explained and set up the learning process that’s important to look at. It’s one of the most important ways you can help students across that river.

2. Use varied teaching activities to help students develop a first layer of knowledge - you can use the same range of activities to help A level students learn that you would use with younger students - but the purpose is not variety, it’s about helping students develop that very important confidence-boosting first layer of knowledge. One of the best things I did in The Tudor Century way back in 1993 was include four decision-making activities as introductions to the four periods within the book. Before they’d done any reading, students faced a number of decisions to take in role as, for example, Henry VII – they had to think, discuss and make choices. That immediately gave students a first layer of knowledge of the new topic – it wasn’t a complete and secure layer of knowledge but enough to help them move on to read about events with more confidence because they recognised events and people from the decision-making task. Giving students that first layer of knowledge is essential for their confidence and survival – expect them to deal with too much knowledge immediately will send some of them tumbling into the river. One of the teacher’s main tasks is to judge how much to put into that first layer.

And it’s not just decision-making activities that you can use for this purpose. They don’t appear in the books but you can use scripted dramas, structured role-plays (which I used regularly with undergraduate history students) and many other activities – you can find an array of these activities HERE … They’re an essential tool for helping your students maintain their balance and confidence crossing the A level river!

3. Use visual metaphors and recording devices - the artwork of Henry VII crossing the stepping stones is also a reminder of the importance of using good metaphors and visual representations of events and visual recording devices such as washing lines, concept maps etc. Illustrations such as the one of Henry VII crossing the river are often worth many minutes of verbal explanation because they capture an idea in a way that’s instantly comprehensible.

Using visual recording devices is just as important - setting students a washing line activity, placing events or topics on a continuum, requires them to make judgements using evidence i.e. they have to think, not ‘just’ acquire information and remember. The result is not just a strong visual summary of what’s been studied but often creates an essay plan. Washing lines, for example, are great for summing up the issues for a ‘To what extent …’ style question.

It’s important to use visuals in both these ways, alongside or instead of text and as the basis for activities – just because A level students have to write words in assessment doesn’t mean they can’t learn via images. The illustrations provide a great way of understanding a concept, issue or topic that they can then read about with more confidence.

There’s a good many examples of such visuals in the Core text books I’ve discussed (see the list at the end of the article) and I used visual recording devices in my The Wars of the Roses book but also HERE … (the focus is on GCSE but is just as relevant to A level) and there are descriptions of a range of teaching techniques HERE …

One final thought in this section – A level books can help teaching even if they’re on topics you don’t teach. The visuals and teaching ideas may well be transferable to the topics you do teach so it’s worth looking at a range of books, not just those on the topics you teach.

The End!

Writing and editing A level books was fun – and extremely rewarding and satisfying. It was a brilliant experience helping teachers write good books and, later, hearing how much the books have been appreciated by teachers. And it was a pleasure working with so many excellent teachers. All in all, writing and editing A level books has been one of the most satisfying and creative things I’ve done.

List of Publications: A level books

The full list of my publications for A Level comprises:

Writing

The Tudor Century 1485-1603, Challenging History series, MacMillan, 1993, 424 pp

The Wars of the Roses, Enquiring History series, Hodder, 2012, 144pp.

Editing

Core Text series – 9 books, Hodder, 1998-2006, between 280 and 450pp

Fascist Italy by John Hite and Chris Hinton

Weimar and Nazi Germany by John Hite and Chris Hinton

The Early Tudors by David Rogerson, Samantha Ellsmore and David Hudson

Russia under Tsarism and Communism 1881-1953 by Terry Fiehn and Chris Corin

Elizabethan England by Barbara Mervyn

Modern America, The USA 1865 to the Present by Joanne de Pennington

England 1625-1660 by Dale Scarboro

Britain 1783-1851: From Disaster to Triumph by Charlotte Evers and David Welbourne

Britain 1851-1914: A Leap in the Dark? By Michael Willis

Enquiring History series – 6 books, Hodder, 2012-2015, 144pp

The French Revolution by Dave Martin

The Vietnam War in Context by Dale Scarboro

Tudor Rebellions 1485-1603 by Barbara Mervyn

British Society since 1945 by Diana Laffin

Italian Unification 1815-1871 by Ed Podesta and Pam Canning

The Russian Revolution by Christopher Culpin

Two other books in this series were edited by Jamie Byrom and Michael Riley.